Placenames stand as sacred markers for cultural identity, weaving together the narratives, traditions, and connections of indigenous peoples like the Kwakwaka’wakw and Coast Salish Pentlatch, E’ikwsən, and K’omoks communities. Through the exploration of placenames within these cultural contexts, we delve into the intricate role placenames play in preserving heritage, fostering identity, cultural connection, and cultural continuity.

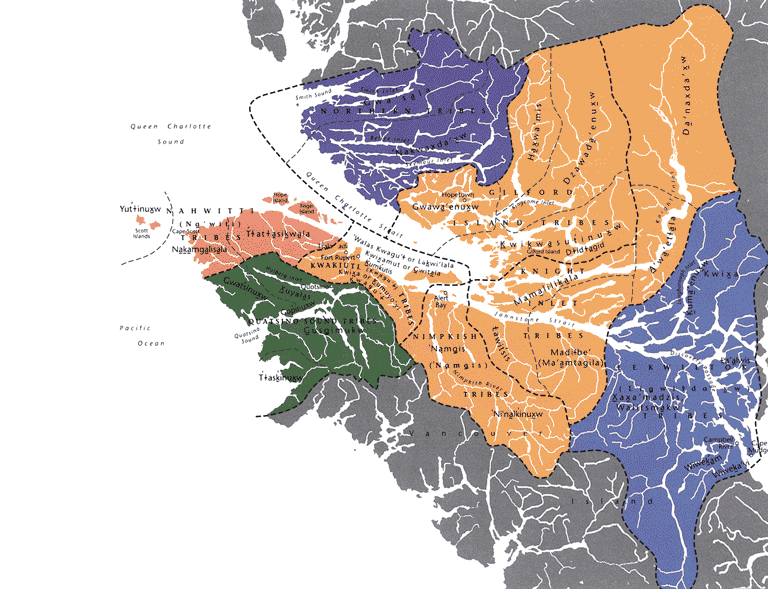

The Kwakwaka’wakw people, inhabitants of the Pacific Northwest Coast of British Columbia, have a rich tradition of placenames that reflect their deep spiritual and ecological connection to ancestral lands. Places like Tłaladi “place of Whales” and Tsamas “Breath In The morning” are not just geographical markers but repositories of ancestral knowledge and cultural significance. These names carry stories of creation, migration, and survival, binding the Kwakwaka’wakw people to their land and to each other across generations. Tsamas was the site where Numas, ancestor of the Kwakwaka’wakw family called Nunemasaqalis, survived the great deluge. Here Numas encountered an eagle-sized butterfly that guided him through the ordeal and bestowed the symbol of the butterfly to be his family crest, acknowledging Numas for his courage, humility, respect, perseverance, and wisdom. When the floodwaters receded, Numas migrated from Tsamas (Mt. Tolmie) in what is known as Victoria today, to Hardy Bay Lake to a site known as ogiwala’a, not to be confused with the placename on Deer Island outside Tsakis (Fort Rupert -Beaver Harbour).

Tłaladi, “The Place of Whales “spouting on the beach,” speaks to placenames for identity, cultural continuity, and cultural connection. Here, the ancestor went up the beach, took his costume off, became a man, declared his name as Tłalis, “spouting on the beach,” and then declared the land as Tłaladi “Place of Whales.” The story marks who named the land and where the first placenames for that land came. Further, “The Place of Whales” marks where the descendants of Tłalis centre their origins. Indigenous people give value to knowing where they come from and who they come from. The name “Spouting On the Beach” informs others of the nature of the ancestor and the current chief who wears that name has a giving and generous nature, a man who shares himself and the abundance found in his territory.

Similarly, the Coast Salish Pentlatch, E’ikwsən, and K’omoks peoples of the Salish Sea region in British Columbia have endowed their landscape with placenames that reflect their intimate relationship with the land and sea. Locations such as Tłamataxw (Campbell River) and Xa’xɛ’əm (Miracle Beach) encapsulate centuries of cultural heritage and ecological wisdom. These names serve as touchstones for the E’ikwsən people, grounding them in their ancestral territories and guiding their stewardship of the environment. The root of Xa’xɛ’əm are words like sacred, holy, miracle. This name is connected to the transformer K’umsnuł, who transformed a female ancestor into the Island Mitlenatch, preserving her qualities of spiritual strength and generosity. Tłamataxw translates to “place of houses,” but when house is viewed as ancestor, the site becomes “The Place of Ancestors.”Moreover, the names of villages, rivers, and mountains evoke memories of shared place, teachings, and ceremonies, strengthening the bonds between individuals and their cultural heritage. For example, the name Pentlatch itself carries the meaning “satiation,” a state of satiety resulting from the food harvested from the land, reflecting the abundance of resources and the resilience of the Pentlatch people in the face of historical challenges. It is a foundational belief of the people that when people treat the land and resources with respect, through reciprocity, abundance is provided in return. To live a life in satiety, the people are living in harmony with the world around them.

Furthermore, placenames within Kwakwaka’wakw and Coast Salish territories are imbued with spiritual significance, reflecting indigenous cosmologies and belief systems. Mountains, rivers, and islands are not merely physical features but sacred sites where ancestral spirits reside and where humans interact with the supernatural world. For instance, the name Kwunwaas (The Place of Thunderbird) locates the ancestor who helped build the first house for the Gigalgam ‘na’mima. “tə̓ gəm Kemos, Sun on Face” of the house, speaks to the house being the ancestor. Further, when entered, the people experience the spiritual world of the ancestor. Wakias went to the mountains, K’ate’mot went to the forest, then climbed deep into the ocean, Ikwsən climbed to the upper world to the home of Chief Moon, and Kwakwasa swam as a salmon in the river Gwa’ni, each to obtain spiritual strength and a treasure to help elevate the spirit of their respective families. In addition, the process of reclaiming and revitalizing traditional placenames is central to the cultural resurgence and decolonization efforts of Kwakwaka’wakw and Coast Salish communities. In recent years, there has been a concerted effort to restore indigenous names to geographical features, reclaiming the narrative of the land from colonial erasure.Placenames serve as vital threads in the tapestry of Kwakwaka’wakw and Coast Salish cultural identity, connecting individuals to their ancestral lands, traditions, and communities. By preserving and revitalizing traditional placenames, indigenous peoples reaffirm their connection to the land and assert their right to self- determination and cultural sovereignty.

In an era of cultural revitalization and reconciliation, placenames stand as enduring symbols of resilience, resistance, and renewal for indigenous communities across the Pacific Northwest Coast.